|

Interference >>

|

|

This unit deals with the effects of electromagnetism – the interaction between electrical charges, currents and magnetic fields. This has proved to be a highly fruitful area of science as it has led to numerous practical applications such as TV’s, radios, motors, generators and the widespread use of electricity in the world. An important scientific application is mass spectrometry, which has been used to weigh molecules, atoms and sub-atomic particles

|

5.1 - Magnets and Electromagnets

Objectives:

- To be able to draw the magnetic field due to a) a bar magnet, b) an electrical current, c) a coil of wire and d) a solenoid.

- To understand how to increase the strength of a magnetic field.

- To know the direction of a magnetic field.

Magnetism is a weird, mysterious and invisible force. We grow up playing with magnets and using them to navigate (well, at least I did), but how many of us understand how they work? Do they run out of magnetism? How are they made?

Basics first!

Basics first!

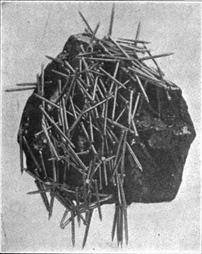

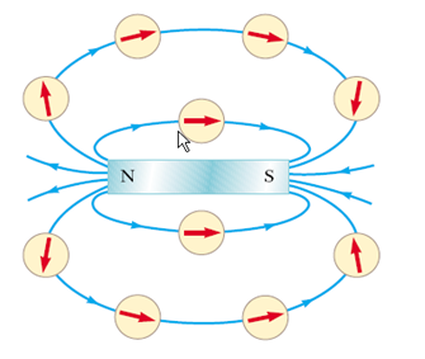

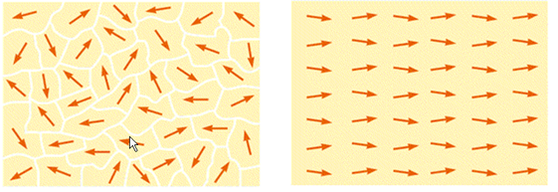

As we should all know by now, opposite poles attract, like poles repel. This seems to be awfully similar to the interaction between electric charges, so that is a clue that electricity must be involved somewhere. The magnet produces a magnetic field around it. This is a region of space surrounding the magnet that anything that is susceptible to a magnetism experiences a force. Materials like this are known as magnetic and there are only three elements that are magnetic: nickel, iron and cobalt. The field can be shown by either using iron filings or a compass. A compass has a magnet that is free to rotate and aligns itself with the magnetic field lines, including those of the Earth.

Note the characteristic pattern of the field lines and how they go from North to South. The poles got their names from the direction that they point when freely suspended. Santa doesn't live at the end of a magnet though. Some interesting facts about magnets:

How do we quantify the strength of a magnet or magnetic field?

Not as easily as you would think is the answer. The crudest method, which we use at middle school and IGCSE, is to measure the mass suspended by a magnet. The greater the mass suspended, the stronger the magnet. However, other variables include the size of the magnet and distance between the magnet and the mass suspended. The material that is suspended also could be a variable - iron would experience a different force to say nickel. Would the geometry or surface area change things too? Would a magnet pick up a long, thin object differently to a short, fat object of the same mass? These are all interesting questions.

Physicists got around these problems by defining a couple of variables; magnetic flux and magnetic flux density (which is far more commonly known as magnetic field strength).

Magnetic Field Strength, \(B\), (or magnetic flux density) is the magnetic flux per square metre area. The unit is the Tesla, named after the Serbo-Croatian genius of ac electricity - not the car company....! The tesla is a large unit. A \(1.0 \,\text{T}\) magnet would be very, very strong. The strongest magnets that you may experience in your life are in an MRI machine and they run to about \(1.5 \,\text{T}\) and are strong enough to jiggle the nuclei of your component atoms. They will also wipe your hard drive and credit card strip at \(20\) paces.... The Earth's magnetic field is of the order of a ten thousandth of a tesla.

Magnetic Flux, \(\Phi\), is the number of magnetic field lines passing through a certain area (e.g. the pole surface of a magnet). It is somewhat hard to count the field lines though, and how would we define their values? So in reality this variable is only used conceptually rather than quantitatively, especially at AP level.

\[\Phi = BA\]

- If you break a magnet in half, you get two smaller and weaker magnets. No matter how small you break the magnet, you will always have a smaller magnet with two poles. The magnetic monopole does not exist. This is a big difference compared to electric charges. This would indicate that magnetism is present at an atomic scale.

- If you heat a magnet over a flame the magnetism is destroyed.

- If you repeatedly bang the magnet the magnetism is destroyed.

- Stroking a magnet repeatedly against a piece of steel or nickel you can create a magnet.

- The Earth has a magnetic field surrounding it, but there is not a magnet inside it. The geomagnetic field is a fascinating area of study and there are still many unanswered questions. Some of the consequences of the field are: navigation - including wildlife migration (how?!), the aurorae, and the reduced concentration of cosmic radiation at the surface.

- The strongest permanent magnets are made from an alloy based on the rare earth element neodymium (ingredients - neodymium, iron and boron) and can lift a thousand times its own weight. These are critical in small, powerful motors, such as those found in hard drives, drones and electric vehicles.

How do we quantify the strength of a magnet or magnetic field?

Not as easily as you would think is the answer. The crudest method, which we use at middle school and IGCSE, is to measure the mass suspended by a magnet. The greater the mass suspended, the stronger the magnet. However, other variables include the size of the magnet and distance between the magnet and the mass suspended. The material that is suspended also could be a variable - iron would experience a different force to say nickel. Would the geometry or surface area change things too? Would a magnet pick up a long, thin object differently to a short, fat object of the same mass? These are all interesting questions.

Physicists got around these problems by defining a couple of variables; magnetic flux and magnetic flux density (which is far more commonly known as magnetic field strength).

Magnetic Field Strength, \(B\), (or magnetic flux density) is the magnetic flux per square metre area. The unit is the Tesla, named after the Serbo-Croatian genius of ac electricity - not the car company....! The tesla is a large unit. A \(1.0 \,\text{T}\) magnet would be very, very strong. The strongest magnets that you may experience in your life are in an MRI machine and they run to about \(1.5 \,\text{T}\) and are strong enough to jiggle the nuclei of your component atoms. They will also wipe your hard drive and credit card strip at \(20\) paces.... The Earth's magnetic field is of the order of a ten thousandth of a tesla.

Magnetic Flux, \(\Phi\), is the number of magnetic field lines passing through a certain area (e.g. the pole surface of a magnet). It is somewhat hard to count the field lines though, and how would we define their values? So in reality this variable is only used conceptually rather than quantitatively, especially at AP level.

\[\Phi = BA\]

5.2 - Electromagnetism

In 1819 Oersted discovered that a wire which is carrying an electrical current deflected a compass needle. He had found that there is a link between electricity and magnetism. This seemingly trivial experiment was only of those discoveries that changed the world. By understanding how electricity and magnetism are interrelated things like electricity could be generated and transmitted on a large scale and even more importantly, used to create motion.

The key part to all this are the wonderful devices called electromagnets.

Students have often made electromagnets and quantified their strength by picking up paperclips. Usually, what they tend to remember most is that if they put too high a current through the wire the plastic covering melts.... oh well, the life of a physics teacher - sigh.

The key part to all this are the wonderful devices called electromagnets.

Students have often made electromagnets and quantified their strength by picking up paperclips. Usually, what they tend to remember most is that if they put too high a current through the wire the plastic covering melts.... oh well, the life of a physics teacher - sigh.

|

\[\mu_{0}= 4\pi \times 10^{-7}\; \text{N/A}^{2}\]

|

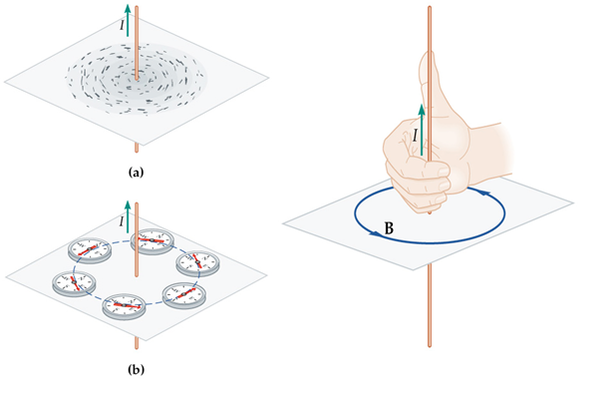

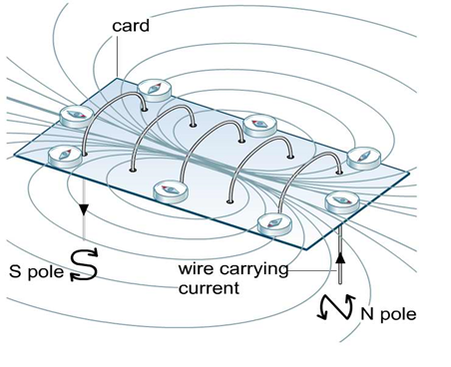

The fundamental concept is that surrounding an electrical current, \(I\), exists a magnetic field, \(B\). This can be shown be either iron filings or a series of compasses. The demonstration for this has to be quick as the effect is weak and needs a high current, which tends to blow the fuses on our power supplies. The direction of the field can be remembered by using the "right-hand screw rule". Learn this!

\[B=\frac{\mu_{0}I}{2\pi r}\] Reasoning: The stronger the current, the stronger the magnet. It can be shown that the magnetic field strength is proportional to the current. The field gets weaker with distance. It can be thought of as spreadover the circumference of the circles - hence the \(2\pi r\) component in the denominator. The magnetic constant, \(\mu_{o}\), is similar to the permittivity of free space met in the last topic. It is called the permeability of free space and has a defined value. As before, the permeability of air is almost the same. It is a measure of how easily the magnetic field can permeate through a material. Question: why the \(4 \pi\)? |

|

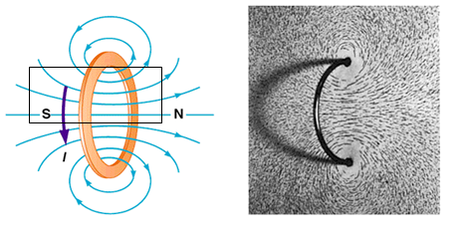

Once Oersted and others figured out that there was a cylindrical field surrounding a current it did not take them long to realise that the effect is vastly magnified if the cylinder is bent into a loop. All of the field lines combine to create a stronger field in the centre of the loop.

\[B=\mu_{0}\frac{NI}{2R}\] |

|

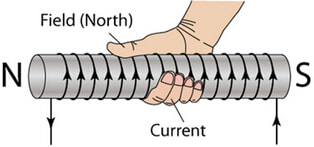

Then, it took them no time at all to take this further and increase the number of loops to form a flat coil and then a long coil (solenoid).The easiest way to figure out which end of an electromagnet is the north pole is to use the same "right-hand screw rule" as earlier. Lay the hand over the electromagnet so that the fingers follow the current around. The thumb points to the north pole of the magnet. There are other methods, but this is the quickest and easiest.

|

|

The strength of an electromagnet can easily investigated and depends on three major variables:

|

\[B = \mu_{o}\frac{NI}{L}\]

|

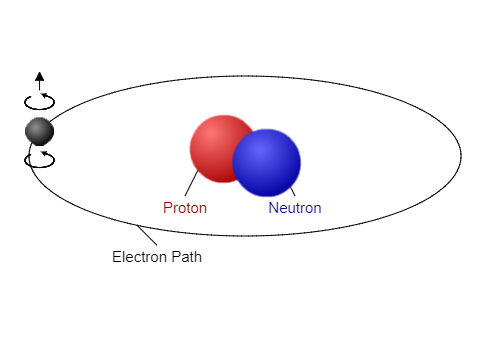

So, what is inside a magnet now that we know that 'bar magnet' type magnetic fields are created by a loop of electrical current?

Ultimately it is the orbital motion of an electron acting as a smaller-than-microscopic loop of current. A current is a flow of electrical charge, and as the electron moves around the nucleus it is producing a tiny magnetic field.

Ultimately it is the orbital motion of an electron acting as a smaller-than-microscopic loop of current. A current is a flow of electrical charge, and as the electron moves around the nucleus it is producing a tiny magnetic field.

5.3 - Force on a Charge in a B-field

Objectives:

- To know that electric charge that is moving in a magnetic field is subject to a force.

- To know how to calculate the magnitude and direction of this force.

- To be able to use this force to solve mechanics problems involving the motion of a charged particle in a magnetic field – such as circular motion.

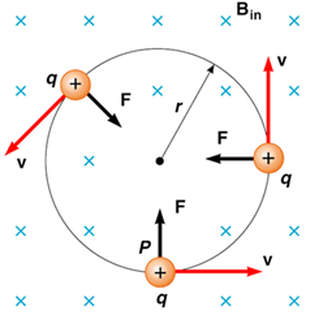

If a charged particle is stationary inside a magnetic field it experiences no force. However, if it is moving it does. This force is mutually perpendicular to the field and the particle's velocity. The force increases if any of the variables of charge, velocity and field strength increase, so therefore the equation is:

\[F = Bqv\]

This equation may need to be modified if the field is not perpendicular to the velocity. Only the perpendicular component of the field causes the force. Use trig to find this component. As the force is perpendicular to the velocity it does not change the speed of the particle, but pulls it around into a circle. (see Unit 3 ). The magnetic force provides the centripetal force required for circular motion.

This is a staggering useful effect for atomic physics and chemistry as it provides us the means to "weigh" molecules, atoms and sub-atomic particles. If we know the charge and speed of the particle, the radius will determine its mass.

\[F = Bqv = \frac{mv^{2}}{r}\]

rearrange to yield:

\[m=\frac{Bqr}{v}\]

Millikan's oil drop provided the final piece of information for the calculation. The velocity can be determined by the voltage needed to accelerate the charged particles.

\[F = Bqv\]

This equation may need to be modified if the field is not perpendicular to the velocity. Only the perpendicular component of the field causes the force. Use trig to find this component. As the force is perpendicular to the velocity it does not change the speed of the particle, but pulls it around into a circle. (see Unit 3 ). The magnetic force provides the centripetal force required for circular motion.

This is a staggering useful effect for atomic physics and chemistry as it provides us the means to "weigh" molecules, atoms and sub-atomic particles. If we know the charge and speed of the particle, the radius will determine its mass.

\[F = Bqv = \frac{mv^{2}}{r}\]

rearrange to yield:

\[m=\frac{Bqr}{v}\]

Millikan's oil drop provided the final piece of information for the calculation. The velocity can be determined by the voltage needed to accelerate the charged particles.

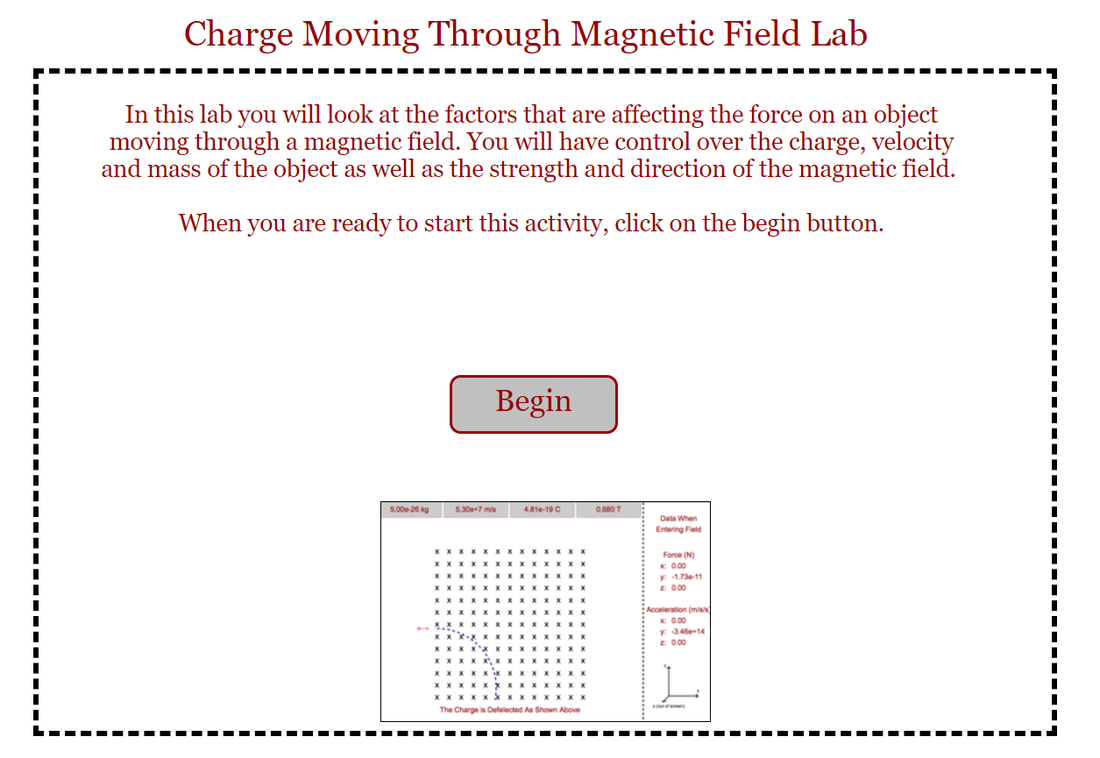

LAB - Measuring the mass of an electron

|

The uniform magnetic field due to a pair of Helmholtz coils that are separated by a gap equal to their radii, which is the normal setup for the fine beam tube, is given by the equation below (don't bother to learn...)

\[B=\frac{\mu_{0}\, 8\, I\,N}{\sqrt{125}\, R} \] The speed of the electron can be calculated from the voltage applied to the electron gun. \[KE = eV=\frac{1}{2}mv^{2}\] putting all of this together we get: \[m=\frac{eB^{2}r^{2}}{2V}\] This is the principle behind the science of mass spectrometry.

|

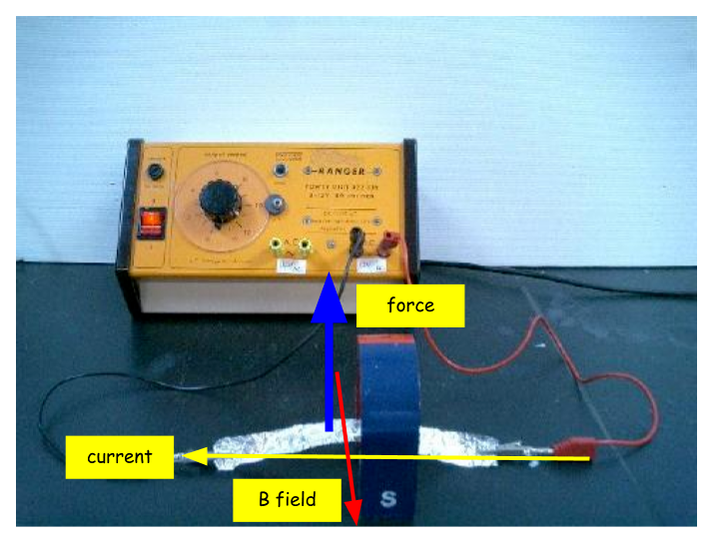

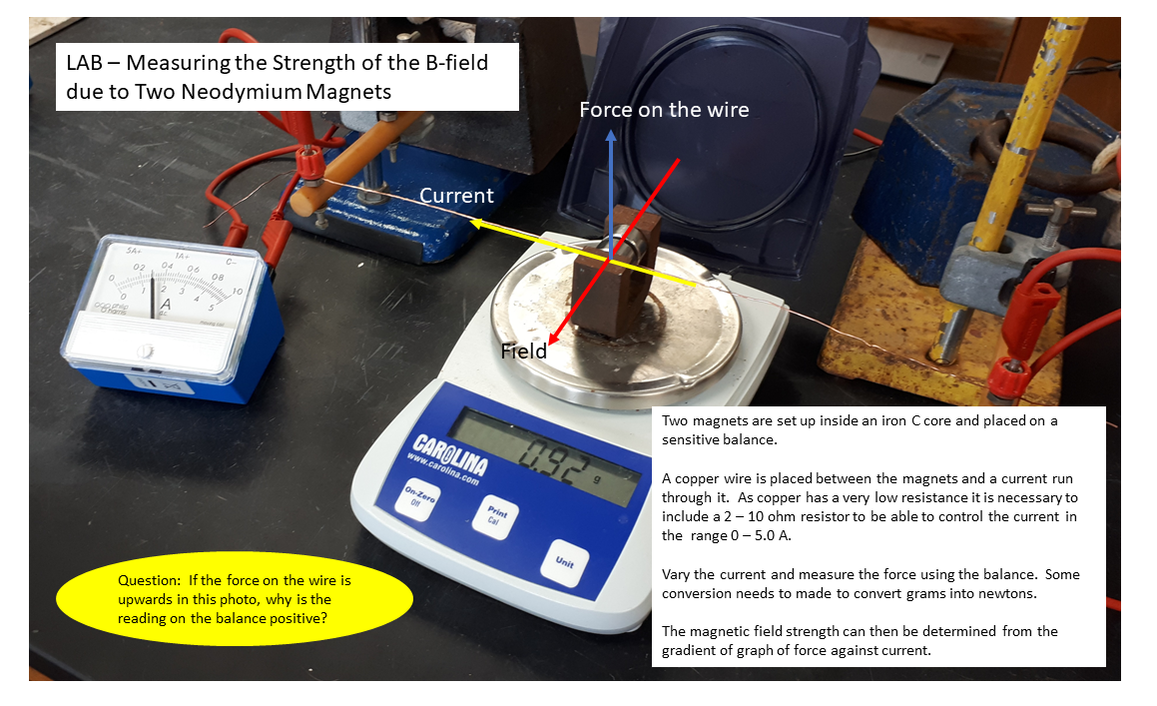

5.4 - Force on a Current Carrying Conductor in a B-field (Motor Effect)

Objectives:

- To know that a conductor carrying a current through a magnetic field experiences a force upon it.

- To be able to calculate this force.

- To know some of the applications of this effect.

- To understand the definition of the ampere.

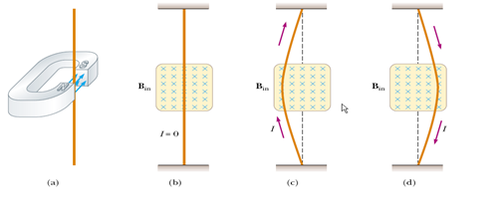

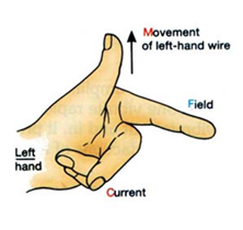

The famous 'motor effect' is the macroscopic version of the previous force. The current in a wire is the stream of moving electrons. Each one of these experiences a tiny force due to their motion in the magnetic field. Add all these forces together and we have a very noticeable force that can be utilised in any situation where we need electricity to create motion. The direction of the force can be determined using the Left-Hand Rule from IGCSE. From basic experiments back in year 11, we have realised that the size of the force can be increased by a) increasing the magnetic field strength, b) increasing the current and c) increasing the length of the wire that is inside the magnetic field. So, the equation for this should not come as a great surprise.... If the current is at an angle to the field the usual sine correction will need to be applied. Only the component of the current that is perpendicular to the field will generate a force.

\[F=\sum{F_{e}}\]

\[F=\sum{Bev}=\sum{Be\frac{x}{t}}=B\frac{Ne}{t}x=BIl \]

\[F=\sum{F_{e}}\]

\[F=\sum{Bev}=\sum{Be\frac{x}{t}}=B\frac{Ne}{t}x=BIl \]

5.5 - Electromagnetic Induction

Objectives:

- To know that a magnetic field moving relative to a conductor will induce an emf (or voltage) across the conductor.

- To be able to calculate the induced voltage in simple situations.

- To be able to calculate the resulting current if a circuit is present.

- To understand the practical applications of this effect.

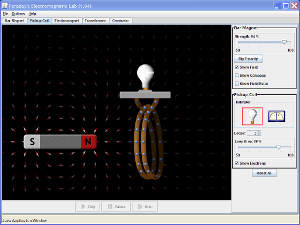

During the IGCSE course it was demonstrated that electricity can be generated by the movement of a magnet inside a coil of wire. By practical demonstrations in conjunction with the PhET Faraday Lab it was clear that the voltage produced depended on three things:

For the higher level physics we need to take this basic introduction further and a) learn what causes it, b) the mathematics behind it and c) how to determine the direction of an induced current.

- Strength of the magnet

- Number of coils of wire

- Speed and direction of the magnet

For the higher level physics we need to take this basic introduction further and a) learn what causes it, b) the mathematics behind it and c) how to determine the direction of an induced current.

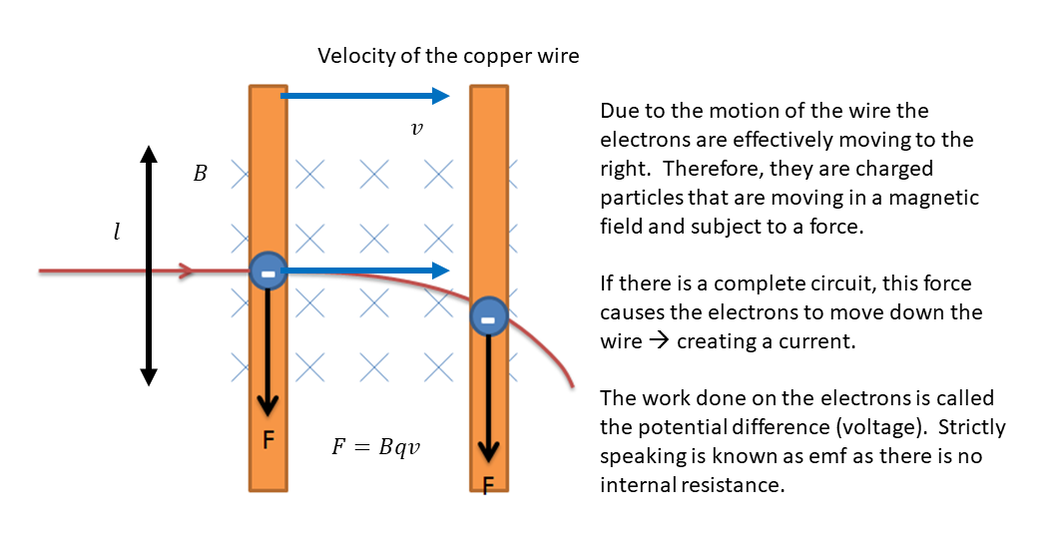

What Causes this "Dynamo Effect"?

If a current is pushed through a motor it spins. Electrical energy is transferred to kinetic energy. However, the opposite is also true. If that same motor is spun by hand it generates electricity. Kinetic energy is transferred to electrical energy. The spoiler to this symmetry is that the current is induced in the opposite direction.

If a current is pushed through a motor it spins. Electrical energy is transferred to kinetic energy. However, the opposite is also true. If that same motor is spun by hand it generates electricity. Kinetic energy is transferred to electrical energy. The spoiler to this symmetry is that the current is induced in the opposite direction.

As the induced emf (voltage) depends on the rate of change of the magnetic field relative to the wire, we will have a differential equation involved. This is simplified quite a bit for the AP-2 course. The overall flux, \((\Phi)\), is a measure of the magnetic field, \((B)\), enclosed within a specified area, \((A)\).

\[\Phi = BA\]

The emf induced is proportional to the rate of change of this flux.

\[\mathcal{E}=-n\frac{d\Phi}{dt}\]

Usually, either the magnetic field or the area is kept constant, so the equation would simplify to one of the ones below, where the constant variable is pulled out of the derivative.

\[\mathcal{E}=-nB\frac{dA}{dt}\]

\[\mathcal{E}=-nA\frac{dB}{dt}\]

Calculus is not required for AP-2, so the simplifications tend to involve a) the field or area changing linearly as a function of time, or b) a single wire being moved at a constant speed through the magnetic field.

Example 1

A coil of radius 5.0 cm is constructed from 10 turns of wire. If the magnetic field strength changes from zero to 1.2 mT in four seconds, calculate the induced EMF.

\[A = \pi r^2 = \pi \times (0.05)^2 = 7.85 \times 10^{-3} \text{ m}^2\]

\[\mathcal{E}=-nA\frac{dB}{dt}\]

\[\mathcal{E}=-10\times 7.85\times 10^{-3} \times \frac{(1.2 \times 10^{-3} - 0)}{4}\]

\[\mathcal{E} = -2.36 \times 10^{-6}\text{ V}\]

Note: the minus sign is purely to indicate the direction of the induced voltage and is rarely considered. The direction of an induced current can be found by applying the right-hand rule or Lenz's Law (next section).

Example 2

A sliding bar, similar to the diagram in your notes, has a length of 0.300 m and moves at 4.00 m/s in a magnetic field of magnitude 0.650 T. Using the concept of motional emf, find the induced voltage in the moving rod.

I would normally start this problem out by sketching a simple diagram, which helps me visualise the set up. The magnetic field stays constant and this time the area changes as the wire moves across the field.

\[\mathcal{E}=-nB\frac{dA}{dt}\]

The area swept out in \(1.0\text{ s}\) is the length of the wire multiplied by the distance travelled due to its motion.

\[A = l \times (vt) = 0.3 \times (4.0 \times 1) = 1.2\text{ m}^2\]

\[\mathcal{E}=-1\times 0.65 \times \frac{(1.2 - 0)}{1}\]

\[\mathcal{E} = 0.78\text{ V}\]

\[\Phi = BA\]

The emf induced is proportional to the rate of change of this flux.

\[\mathcal{E}=-n\frac{d\Phi}{dt}\]

Usually, either the magnetic field or the area is kept constant, so the equation would simplify to one of the ones below, where the constant variable is pulled out of the derivative.

\[\mathcal{E}=-nB\frac{dA}{dt}\]

\[\mathcal{E}=-nA\frac{dB}{dt}\]

Calculus is not required for AP-2, so the simplifications tend to involve a) the field or area changing linearly as a function of time, or b) a single wire being moved at a constant speed through the magnetic field.

Example 1

A coil of radius 5.0 cm is constructed from 10 turns of wire. If the magnetic field strength changes from zero to 1.2 mT in four seconds, calculate the induced EMF.

\[A = \pi r^2 = \pi \times (0.05)^2 = 7.85 \times 10^{-3} \text{ m}^2\]

\[\mathcal{E}=-nA\frac{dB}{dt}\]

\[\mathcal{E}=-10\times 7.85\times 10^{-3} \times \frac{(1.2 \times 10^{-3} - 0)}{4}\]

\[\mathcal{E} = -2.36 \times 10^{-6}\text{ V}\]

Note: the minus sign is purely to indicate the direction of the induced voltage and is rarely considered. The direction of an induced current can be found by applying the right-hand rule or Lenz's Law (next section).

Example 2

A sliding bar, similar to the diagram in your notes, has a length of 0.300 m and moves at 4.00 m/s in a magnetic field of magnitude 0.650 T. Using the concept of motional emf, find the induced voltage in the moving rod.

I would normally start this problem out by sketching a simple diagram, which helps me visualise the set up. The magnetic field stays constant and this time the area changes as the wire moves across the field.

\[\mathcal{E}=-nB\frac{dA}{dt}\]

The area swept out in \(1.0\text{ s}\) is the length of the wire multiplied by the distance travelled due to its motion.

\[A = l \times (vt) = 0.3 \times (4.0 \times 1) = 1.2\text{ m}^2\]

\[\mathcal{E}=-1\times 0.65 \times \frac{(1.2 - 0)}{1}\]

\[\mathcal{E} = 0.78\text{ V}\]

5.6 - Lenz's Law

Objectives:

- To understand the limitations imposed by Lenz’s Law

- To be able to use Lenz's Law to determine the direction of an induced current.

Moving a magnet into a coil of magnet produces electricity - this is magic. We make use of this effect to generate electricity on a massive scale in power stations or on a tiny scale when we read data from a hard drive of a computer or the black stripe from a bank card when getting cash out of the ATM. But it comes at a cost. It is hard to move the magnet or coil of wire. As more current is produced the harder it gets to keep the system moving. Fundamentally, this is due to the Second Law of Thermodynamics - we can't get the same useful energy out as we put in, the system will never be 100% efficient. So why does it get harder?

The motor effect produces a force when a current is moving in a magnetic field.

The dynamo effect produces a current when a conductor is moved in a magnetic field.

Even though these two effects are essentially caused by the same reason - a moving charge in a magnetic field experiences a force, they work in opposite directions to each other (hence the minus sign in the EM induction equation). The wire is moved in a magnetic field, which induces a current. This current that is flowing in a magnetic field produces a force - BUT in the opposite direction to the motion of the wire. The motor effect produced by the induced current tries to stop the motion that has created it. The more current that is produced the stronger the force that opposes the original motion. To keep the wire moving a force has to be applied to counterbalance the motor effect force - force over a distance is work. Work must be done to generate a current.

Another way to look at this is to consider a magnet moving into a coil of wire. As the magnet moves in a current is induced in the coil. The coil then becomes an electromagnet. The pole of the electromagnet facing the incoming magnet is the same as that of the magnet - it is trying to repel the incoming magnet.

The upshot of all this is that you cannot put an alternator on a electric car to charge its battery as it moves. Another is that as we turn on more and more lights, BELCO must put more and more fuel into its engines to generate the required electricity.

The motor effect produces a force when a current is moving in a magnetic field.

The dynamo effect produces a current when a conductor is moved in a magnetic field.

Even though these two effects are essentially caused by the same reason - a moving charge in a magnetic field experiences a force, they work in opposite directions to each other (hence the minus sign in the EM induction equation). The wire is moved in a magnetic field, which induces a current. This current that is flowing in a magnetic field produces a force - BUT in the opposite direction to the motion of the wire. The motor effect produced by the induced current tries to stop the motion that has created it. The more current that is produced the stronger the force that opposes the original motion. To keep the wire moving a force has to be applied to counterbalance the motor effect force - force over a distance is work. Work must be done to generate a current.

Another way to look at this is to consider a magnet moving into a coil of wire. As the magnet moves in a current is induced in the coil. The coil then becomes an electromagnet. The pole of the electromagnet facing the incoming magnet is the same as that of the magnet - it is trying to repel the incoming magnet.

The upshot of all this is that you cannot put an alternator on a electric car to charge its battery as it moves. Another is that as we turn on more and more lights, BELCO must put more and more fuel into its engines to generate the required electricity.

ACTIVITIES

| hw_14.2_-_force_in_a_b-field.docx | |

| File Size: | 51 kb |

| File Type: | docx |

| hw_14.3_-_electromagnetic_induction.docx | |

| File Size: | 33 kb |

| File Type: | docx |

|

|

|

Other Resources

|

PhET simulation - EM lab

|

Learn AP Physics: Magnetism - great website loaded with videos and multiple choice questions

CK12 - Electromagnetism - website with large collection of videos

|

|

|